I got into an argument with my favorite bartender recently about the genius of Baz Lurhmann. His argument was Moulin Rouge. My counterpoint was The Great Gatsby.

Ahem.

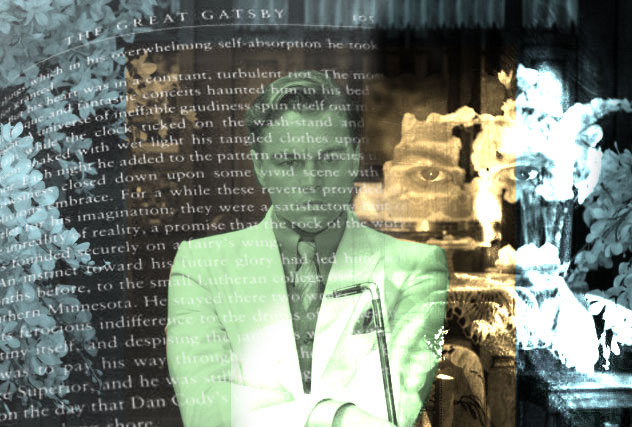

Baz Lurhmann’s The Great Gatsby is heartwarming tale of how a writer-director can take what is arguably the most American novel of all time and transform it to a staggering monument of cinematic piss. At 2 hours and 23 minutes, the film is a bloated psychedelic music video that is bookended by the frame narrative of Nick Carraway writing the book while being treated for alcoholism in a sanatorium.

While certain critics will defend this retcon as an innovative insight into F. Scot Fitzgerald’s life, which indeed spiraled into alcoholic chaos, it’s important to note that Fitzgerald wrote Gatsby in Europe, relatively comfortably, and that it was, in fact, Zelda Sayre who actually wrote a book while in psychiatric care.

You could say the use of the frame narrative device is similar to that of the cinematic adaptation of Naked Lunch, but that argument does not hold an ounce of water (or… gin?)–the film Naked Lunch is a schizophrenic journey of pornographic, junkie appetites that desperately needed narrative grounding, whereas The Great Gatsby is already a complete narrative, rendering any additional storytelling device unnecessary.

It’s kind of frustrating when you read Luhrmann thoughts on his own direction:

“What scenes are absolutely fundamental to the story? What scenes must be in our film? And what scenes can we do with out, even if we love them?”

Luhrmann isn’t really known for discipline in his movies. And that’s fine. He’s about spectacle and I can respect that. But when you pair the above quote with the one below, from the same interview, my mind explodes:

“in the novel, Fitzgerald very deftly alludes to the fact that Nick is writing a book about Jay Gatsby in the book […] – “Reading over what I have written so far…” So Craig and I were looking for a way that we could show, rather than just have disembodied voiceover throughout the whole film, show Nick actually dealing with the writing[…]”

That’s a wide reach to justify the choice of framing the narrative in the film. If I had to guess, Baz either wrote (or directed) his way into a corner, and the focus on Nick Carraway was his solution. I respect that writing involves a lot of creative solutions for the problems you give yourself and a frame narrative might actually be helpful. I’ll even say that the subdued shots of a novel being organized was some of my favorite imagery used in the film, because I’m a gigantic dweeb.

But I’ll take this explanation to task as the Nick storyline is the very definition of visual “telling” and not showing. It’s making literal what was initially implied. Many book adaptations mention that the narrator wrote the book that you hold in your hands– without having to wedge apocryphal material in to justify it.

And if you want an example of perfectly adapting a narrator into a film, look no further than Netflix’s A Series of Unfortunate Events. Which proves that it’s doable without coming off as heavy-handed.

But maybe I’m bitter because when I watched Gatsby in 2013, I left the theater angry because the novel I was working on at the time began with a frame narrative taking place in a psychiatric hospital. When I saw the trope play out on screen, it came off as cheap and melodramatic. I changed it immediately as soon as I got home.

Why did it come off as cheap? How did the device actually change the story?

In Gatsby, the frame device put a lot of weight on the story itself– that’s what a frame narrative does, looking back to a time with a different perspective– and shifts the perspective of the interior story away from a ruminative reflection on the foibles of greed, the emptiness of shallow relationships, the tedious culture of high society and the meaninglessness of achieving the American dream through ill-gotten gains to a brooding, traumatized perspective that undercuts the significance of anything else.

But in the end, The Great Gatsby (2013) got 48% on Rotten Tomatoes, which is a score a high school English teacher would give a book report presentation if it was just Baz Luhrmann nodding along silently as a Jay-Z album played through.

Then again, Robert Redford’s 1973 Gatsby vehicle got 39%. The one in 1949 has a score of 38%.

Maybe we should just leave Gatsby alone.