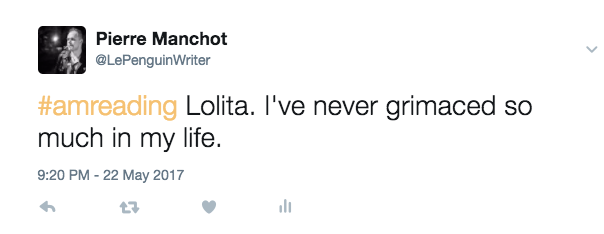

The task of characterization is multi-faceted. The classic advice says to make your protagonist “likable.” Enough literary evidence exists to negate that claim. I’m reading Lolita right now and I hate Humbert Humbert.

I think you can shuck “likable” and instead focus on “relatable.”

I’m going to focus on Lolita in a future post, but for now I’ll raise the question: is Humbert Humbert relatable? Despite being a monster, he seems aware of his own monstrosity– which is why we hate him. He knows better and he continues to act in his deplorable self-interest. While Humbert lays down a lot of unreliable justifications for his behavior, there is a steady thrum of self-loathing under-riding his confession. Humbert hates himself as much as the reader, and that’s what makes that book, ultimately, readable.

I’ll focus on the question: how do you affect relatability in fiction?

The classic advice is to give your character’s an Achille’s heel. No one wants to read about invincible characters. Superman is the classic example of a character so strong, the writers had to contrive a series of convolutions to make him vulnerable, which usually made him seem more improbable and cartoonish. The Watchmen had a clever take on the Superman surrogate, the god-like Dr. Manhattan, by rooting his story in his depersonalization– he distances himself to the point that he no longer can empathize with the human beings he protects and sees their struggle as merely a problem with cold and precise solutions.

It’s in that psychological development that the reader can, ironically, relate to Manhattan. Everyone’s gotten so sick of all of the terrible things that human beings inflict on each other that they retreat from society for a while– there’s a reason people vacation on solitary beaches and stare at nothing for hours on end, the same way Manhattan disappears to Mars and creates intricate statues (for lack of a better term) that have been unfouled by man.

But to the point I’m driving at, relatability becomes more intriguing when you expose the character’s psychological insecurities, instead of their physical limitations. In Sin City, the badass Marv takes a moment of pause, crying along a bridge when he realizes the scope of the evil he’s dealing with. In David Wong’s John Dies at the End, the character of David Wong takes a moment to reflect on his own fragile masculinity in a moment of weakness only hinted at previously. Silence of the Lambs takes this notion and applies a meta-literary tactic of Dr. Lector specifically needling Starling’s insecurities out of her. Think about Harry Potter and how the fifth book underlined Harry’s hormonal dickishness to round out what had previously been a squeaky clean character.

It’s an effective device because while everyone desires the fantasy of being powerful and in control of their own world, everyone has a shadowy valley that cuts through their ego. It’s in that acknowledgement of common fear, doubt, anger, jealousy and self-detrimental habit that the reader can attach their struggle to the hero’s. And that makes the victory that much more rewarding when the hero is finally victorious.

The other major benefit of diving into psychological insecurities is that it builds the internal conflict. While not always necessary, effective pieces utilize the inner turmoil of the protagonist concurrently with the external.

Think about Fight Club which demonstrates this in a very literal sense– the protagonist has become depersonalized and spiritually vacant to the point to which he creates an alternative personality that is capable of achieving everything that the narrator cannot. Superficially, it’s a realization of one’s own potential. Cynically, it might come off as “the magic was inside you the entire time.” In a slightly deeper read, however, one remembers that everything has to do with a girl named Marla Singer. Other passages/scenes (I’m borrowing a lot from Fincher’s film adaptation) indicate a fear of forming a family– specifically the bathtub scene in which the mutual resentment of the narrator’s/Tyler’s father is redirected towards a rejection of women (finding a wife, settling down, “setting up franchises,” “I can’t get married, I’m a 30 year old boy.”); the chemical burn scene that redirects the paternal resentment into a resentment towards God (which should indicate that this resentment and fear of cyclically becoming what you resent literally rules over the narrator’s internal conflict).

Of course, there are undeniable homoerotic undertones to the story, but as far as I can tell from interviews and essays with Chuck Palahniuk, the driving motivation of the narrator is attempting to find a reconnection to the familial world. Also, because the story ends like this: once the narrator accepts his responsibility for the actions (and desires) of his shadow-self and violently cleaves him from existence (indicating the climax of a maturation plot), the narrator and Marla Singer come together, stunned at the destruction of the city scape, seemingly with the narrator finally coming to terms with his adulthood and no longer allowing his fear of his own masculinity to keep him from entering an actual relationship with a girl he fancies.

That’s the film version which, as Palahniuk admits, is thematically more complete. I haven’t read the graphic novelization that serves as the sequel, so I can’t say how that all shakes out. The point is the reason that the narrator, who’s kind of despicable and pathetic in a lot of ways, is able to maintain an effective through-line that engages the audience is that there is an internal conflict that is subtly suggested throughout the novel/film that resonates with nearly everybody in the audience. Most people, I think, harbor anxieties about the reality of becoming an adult and making the same mistakes that their parents imprinted onto them. Fight Club is able to take that and make it into a pretty radical story about punching the Christ out of your buddies and blowing up coffee shops.

And if you can find a way to sublimate your character’s deep-seated intentions in such a way to drive the external plot along? Without the reader necessarily realizing it?

Nobel prize, here you come.